Ebola

Background

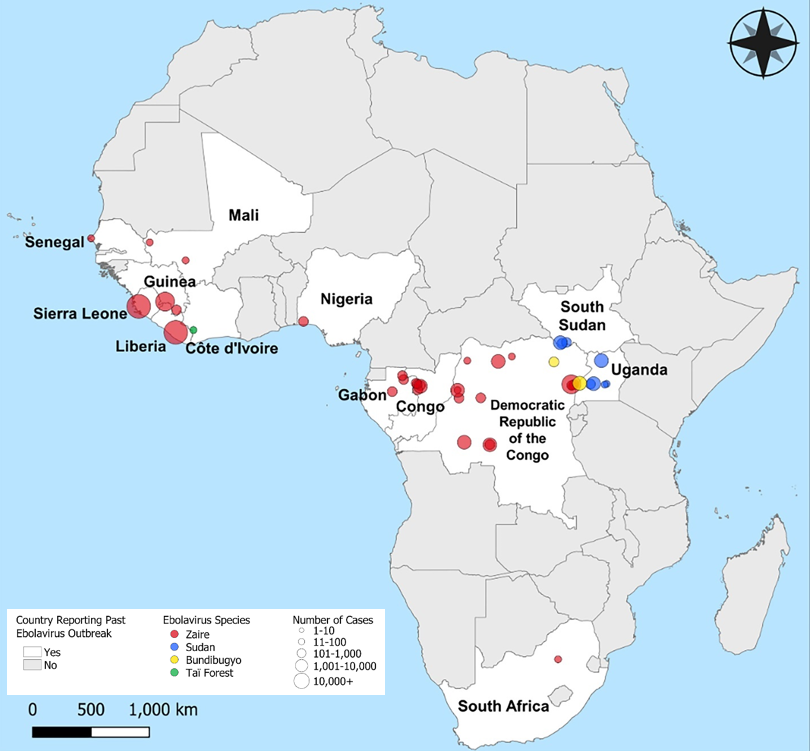

Ebolavirus Outbreaks

Outbreaks occur in areas of Africa where ebolaviruses are endemic (Fig 1). The ebolavirus most commonly associated with outbreaks is Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV). Ebolaviruses are known to cause illness in non-human primates and humans, but bats are thought to be the animal reservoir of these pathogens based on biological and environmental niche research, although the exact species remains unknown. There are no known animal reservoirs of ebolaviruses in the U.S., but EVD can be acquired while living, working, or traveling in areas experiencing an ongoing outbreak or where the virus is endemic.

EVD Transmission

EVD is not generally spread from person to person through casual contact or by inhalation of viral particles in the air. Infection occurs through direct contact with body fluids that include, but are not limited to blood, urine, saliva, sweat, semen, breast milk, vomit, and feces. These viruses can enter through open cuts, scrapes, or other non-intact skin, or mucous membranes (e.g., lining of mouth, eyes, or nose). You can also get EVD by ingesting infectious blood or body fluids including meat from an animal infected with ebolavirus.

The risk of infection from ebolaviruses is minimal if you have not been in close contact with the body fluids of an infected animal or a person sick with or recently deceased from EVD. However, the virus is capable of causing infection for several days in wet or dried body fluids. Surfaces and materials that may be contaminated with blood and body fluids should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected.

EVD Symptoms

Individuals who acquire EVD develop symptoms between 2-21 days after exposure. EVD is believed to be contagious once an individual begins to show symptoms. Persons having close contact with someone who is sick with EVD or with their body fluids have the highest risk for exposure, however exposure is also possible from tasks involving mechanically generated aerosols.

EVD is usually marked by fever, muscle pain, headache, and sore throat. As the infection progresses, patients often experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and impaired organ function. A rash and severe internal/external bleeding may occur as the blood loses its ability to coagulate and blood vessel membranes become more permeable. EVD is fatal in about 50% of human infections.

Because symptoms of EVD may appear consistent with many other illnesses (e.g., influenza, malaria), diagnosis and treatment of EVD could be delayed during an outbreak.